|

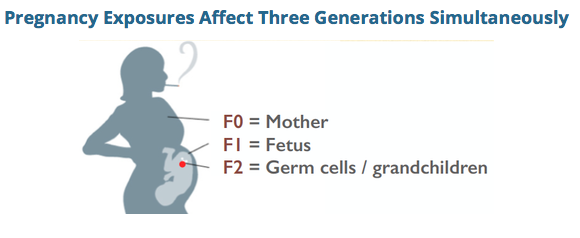

Hello friends, My name is Jill Escher. I'm a science philanthropist who kickstarts pioneering research projects investigating the generational toxicity of certain potent exposures, including DES, tobacco and other drugs. While I'm not a DES daughter, I was exposed to a multitude of other synthetic steroid hormones in utero as part of a then-popular, if ineffective, "anti-miscarriage" practice. You can read my story here. You can see my science website at GermlineExposures.org. Based on human, animal, and in vitro studies, as well as family interviews, I hypothesize that DES, along with several other toxic substances, can damage the genomic information in early fetal-stage gametes. For a variety of reasons, the early gamete is probably the single most vulnerable stage of the human lifecycle. Damage during that phase, which could be genetic or epigenetic in nature, can manifest as abnormal development in the subsequent offspring. For example, I hypothesize that the intensive synthetic steroid hormone drug regimen to which I was subjected as a fetus subtly deranged the molecular programming of my early eggs. This derangement I believe resulted in the starkly abnormal neurodevelopment — autism — of my children. I have met many other families with the same story. I am pleased to announce that I am funding the world's first research study into the grandchild effects of DES (3d gen), looking specifically at neurodevelopment and behavioral impacts. This work will be done in collaboration with Harvard University, based on the Nurses' Health Study II. If you can support this work, please contact us. Thank you for your support! If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to reach me at: jill.escher@gmail.com

0 Comments

Autism’s missing link? Study family history alongside genetics Can exposures during our own prenatal development affect our children? This mom and autism advocate is funding research to find out By Jill Escher, founder of the Escher Fund for Autism. Jill has two children with autism and is a longtime supporter and collaborator with Autism Speaks. The dominant idea in autism research today is that the causes of autism are largely genetic. As a result, funding for autism research has emphasized hunting around DNA for clues. I agree this is essential. However, to my mind, it’s also incomplete. It's not enough to draw blood and sequence our genes. We should put equal effort into investigating family histories. Why our histories? To be blunt, our histories are not just about us, they’re also about our sperm and eggs – our gametes – the raw material that give rise to our children. Remember learning in biology class that “a girl is born with all her eggs?” Our gamete-producing cells, in both males and females, didn’t develop in a vacuum: They tangoed with environmental exposures, starting in our mothers’ wombs. Looking beyond DNA You probably know of obvious exposures that can affect genes. Examples include carcinogens such as tobacco smoke and mutagens such as X-rays. Both can directly damage DNA. In addition, emerging research shows that some drugs and other chemicals (including so-called “endocrine disruptors”) can modify how our genes operate without altering their underlying DNA code. This is the science of epigenetics, the study of mechanisms that control how genes turn on and off at the proper time and place. Our gametes are vulnerable to a variety of environmental influences, and their vulnerability can set the stage for disorders and diseases. Let me offer a hypothetical illustration about how this might work. Say a medical treatment for children involved repeated X-rays of the abdomen. That radiation could cause genetic errors in the children’s egg- or sperm-progenitor cells. As a result, their offspring, born decades later and conceived of those cells, might have higher rates of certain genetic disorders. Now, I will argue that other, perhaps less obvious, gene-environment interactions may be tinkering with our genes. Take my family history as an example. My husband and I have two autistic children, ages 17 and 10. We have no family history of autism or mental disorders. The conceptions, pregnancies and deliveries were entirely normal with no notable risk factors. The kids are robustly healthy, and genetic tests have failed to show anything amiss. But their brains clearly did not wire up in the typical fashion. They remain severely challenged and nonverbal to this day. Are their genes alone to blame, or is there something more? I believe that autism research is entering a new era where we no longer look at genes and environment in isolation. Our family stories will be instrumental in breaking new ground and solving some of autism's deepest mysteries. Exploring my own prenatal exposures Several years ago, I discovered some troubling news about my own history. I obtained detailed medical records showing that during my mother’s pregnancy, I was prenatally exposed to heavy and continuous doses of powerful synthetic steroid hormone drugs. At that time, some doctors used many of these drugs (these were endocrine disruptors, or hormone mimics) to prevent miscarriage – though it turns out they were ineffective, and in many cases, profoundly damaging. Now you might be thinking, what a weird idea that medications that my mother took during pregnancy with me in 1965 could cause developmental problems in my children decades later. It might make sense if you consider that my early egg cells were already present when I was developing in my mother’s womb. Could the fake hormones given to my mother have disrupted the normal process of reprogramming in my budding egg cells? If so, molecular glitches in my eggs might manifest as dysregulations of development decades later, after my children were conceived and then missed their early milestones. Some researchers have termed this the "time bomb" hypothesis, because of the proposed delayed effect of gamete, or germline, exposures that occurred decades before. In recent years, I’ve met many autism parents with similar in utero exposure histories – some involving pharmaceuticals, tobacco or illegal drugs. I’ve grown particularly concerned about the fetal germline impacts of all the heavy pregnancy smoking of the 1950s through 1970s. Though pregnancy drugs and smoking were rampant in those decades, few people have asked about the health and development consequences to the generation exposed as gametes. There are plausible connections to dysregulation of neurodevelopment. However, a plausible connection is not enough. It's just a place to start. Now we must move forward with serious research investigating the possibility of such gene-environment interactions. To kick-start this area of research, I support pilot projects through a grant program, in addition to my education and advocacy work. Collaborating with Autism Speaks I've also found a wonderful collaborator in Autism Speaks. Already, Autism Speaks and the Escher Fund for Autism have sponsored, with the UC Davis MIND Institute, the first scientific symposium on Environmental Epigenetics in Autism. Now Autism Speaks, the Escher Fund and the Autism Science Foundation are sponsoring an ongoing, free webinar series probing epigenetics and gene-environment interactions in autism. Autism Speaks also funds a number of innovative research projects exploring the epigenetics of autism. I believe that autism research is entering a new era where we no longer look at genes and environment in isolation. Our family stories will be instrumental in breaking new ground and solving some of autism's deepest mysteries. To learn more, also see: “What is epigenetics and what does it have to do with autism,” in the Autism Speaks “Got Questions?” advice column. Environmental Epigenetics Webinars co-sponsored by Autism Speaks, Autism Science Foundation and Escher Fund for Autism By Jill Escher

There is increasing appreciation that a subset of ASDs may be driven by heterogenous de novo errors in the germline (egg or sperm leading to the conceptus) or early conceptus, and also that epigenetic errors might be at play in some forms of autism. It seems reasonable to ask the next question, if there exist such molecular glitches in the germline, might they have been precipitated by certain mutagenic or epimutagenic exposures? As evidence mounts that autism is strongly heritable but not strongly genetic in the Mendellian sense, these questions appear to be increasingly reasonable. My work promoting gene-environment investigation in autism etiology is based in part on my own story. As an embryo and fetus was heavily exposed to a variety of synthetic steroid hormone drugs that were part of a popular, yet ineffective, "anti-miscarriage" protocol of the 1960s. I hypothesize these acute exposures induced subtle molecular errors, likely of an epigenetic nature, during reprogramming in my vulnerable early oocyctes, resulting in the delayed phenotypic consequence of my children's severe yet idiopathic dysregulated neurodevelopment (labeled as autism), decades after the exposure itself. I have found numerous autism families with strikingly similar evolutionarily novel exposures and strikingly similar unexplained pathologies in their offspring. But as I interviewed autism parents to investigate their prenatal histories, another exposure kept popping up. Over and over I would hear comments like: "No I don't think my mom took any drugs when she was pregnant with me, but she smoked like a chimney," or "My mother chain-smoked, so did my dad, and my mom kept smoking all the way through labor." At first I paid little attention to these anecdotes as I considered cigarette smoking to be mundane and harmless relative to the potent geno-affective chemicals to which I had been exposed. But in my interviews, stories of "grandma's smoking" and often grandpa's too, began to display an strong pattern, even though I started my interview project not remotely interested in this exposure. Grandmaternal cigarette smoking makes scientific sense in relation to de novo germline errors When one considers the well-established mutagenic effects of tobacco smoke, in combination with the critical developmental window of fetal germline synthesis, when the germline is stripped of methylation and dynamically remodeled, the biological plausibility of the hypothesis begins to add up. High toxicity. Tobacco smoke has many toxic and mutagenic components. There is also growing appreciation for its epimutagenic effects. Components of concern include BaP, nicotine, tar, formaldehyde, and benzene, not to mention additives and even pesticide and radiation residues. Research has shown that tobacco smoke and/or its constituents cause increased rates of mutation in gametes. DeMarini, in "Declaring the existence of human germ-cell mutagens," Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis 2012, states that many studies have shown cigarette smoke to be a somatic-cell mutagen, and is genotoxic to oocytes and sperm of smokers. Marchetti et al, in "Sidestream tobacco smoke is a male germ cell mutagen," PNAS 2011, reflected that cigarette smoking increases oxidative damage, DNA adducts, DNA strand breaks, chromosomal aberrations, and heritable mutations in sperm. The study showed that short-term exposure to mainstream tobacco smoke or sidestream tobacco smoke (STS), the main component of second-hand smoke, induces mutations at an expanded simple tandem repeat locus (Ms6-hm) in mouse sperm. Passive exposure to cigarette smoke can cause tandem repeat mutations in sperm under conditions that may not induce genetic damage in somatic cells. Recent work by Yauk et al (unpublished) in a mouse model suggests increased rates of somatic mosaicism as a result of male germline exposure to benzo(a)pyrene, a mutagenic component of cigarette smoke, exposure. A recent study from the NIEHS, "DNA Methylation in Newborns and Maternal Smoking in Pregnancy: Genome-wide Consortium Meta-analysis," http://www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297%2816%2900070-7, found more than 6,000 differentially methylated CpG sites in newborns of mothers who smoked during pregnancy. Germline damage demonstrated. With respect to F1 paternal smoking, studies have shown reduction of quantity and quality of sperm in tobacco-using males, including a mouse study by Yauk finding changes in the DNA sequence of sperm cells. See Yauk et al, Mainstream tobacco smoke causes paternal germ-line DNA mutation, Cancer Res. 2007. Why examine early germline exposure instead of closer to the time of conception? As autism researchers increasing turn attention to gene-environment interactions in autism etiology, there have been efforts to seek "pre-conception" exposure data in certain cohorts. While this is a positive development, it ignores the biological reality that the most vulnerable period of germline development is the earliest phase (ie, in the embryo, fetus, and neonate) in which the dynamic rearrangement of germline epigenetic reprogramming, including the laying of imprints, occurs. As with somatic development, the germline, too, has "critical windows" in which vulnerability to exposures is more acute than in other phases. With respect to proximal exposure of the fetal brain, as opposed to germline, though fetal smoking exposure is associated with a wide variety of adverse outcomes and birth defects, there appears to be no evidence to support a measurable association between maternal prenatal smoking and ASD in offspring. See Rosen et al, "Maternal Smoking and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis," Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2015. However, germline exposure effects have not been probed. This could be a "smoking gun" In the big picture of potential mutagenic and epimutagenic agents, why focus on F0 cigarette smoking, instead of, say, synthetic sex steroid drugs or general anesthesia, which are two of the other potent prenatal exposures which repeatedly came up in the autism family interviews? Here are two reasons, aside from the known mutagenicity aspect: High prevalence. F0 maternal smoking appears to have been one of the most prevalent and acute toxic exposures during the timeframe in which the new generation of autism parents—and their germ cells—were in utero. Up to 40% of women smoked at the peak of the late 1960s. Furthermore, the exposure was often heavy—5,400 cigarettes through gestation for a pack-a-day smoker. Ease of ascertainment. It is easier to ascertain F0 smoking than use of other medications or medical interventions, simply because smoking would remain in the recollections of family members. (For example, I would not have known anything about my in utero exposures were it not for the exceptionally rare circumstance of having obtained detailed records of pharmaceuticals given to my mother while pregnant with me. My mother never told me about the medications, and did not smoke.) Let's get this research party started Sensing that high rates of maternal smoking in the second half of the 20th century may have unanticipated but lasting genomic consequences, Escher Fund for Autism seed funded a number of small pilot studies (for example, Denmark Prenatal Development Project cohort, CHDS cohort, UK ALSPAC cohort) that can begin to probe potential grandchild (F2) neurodevelopmental sequelae of grandmaternal (F0) smoking, via child (F1) prenatal smoking exposure. It will likely take years for pilot data to be sorted out. In addition, none of these projects are based on cohorts of autism subjects for whom we have genomic data. Escher Fund is also communicating with other researchers in an attempt to persuade them to examine F0 smoking as a variable in their autism cohorts, including: Australia Autism Biobank MSSNG (University of Toronto, Autism Speaks) Kaiser Autism Family Genetics Study (Kaiser) Korean Autism Cohort study (UCSF) African American autism cohort (UCLA) CHARGE study (UC Davis) Some observations from my interviews with autism families Based on my many interviews with autism families in which at least one biological grandmother had smoked heavily during pregnancy, I'd like to offer some preliminary observations: --The families had no prior history of autism --ASD cases where grandmother was a heavy smoker tend to be severe and nonverbal--perhaps there is a dose-response effect --The ASD is usually sporadic among siblings, but often siblings have other pathologies such as ADHD or learning disabilities --Sometimes F2 cousins descended from the same F0 grandmother who smoked have ASD --The grandfather was often a smoker too, meaning second-hand smoke could be a factor --There seem to be more multiplex F2 ASD children in African American families where a grandmother had smoked --Where F0 paternal grandmother had smoked, F1 father had smoked, and F1 father was of an older age, the risk for ASD in the F2 offspring seems to be markedly higher I hope more and more autism research can focus on this question of germline exposure to cigarette smoke, rather than continuing down the path of "genetics in a vacuum." My hunch, after conducting about 200 autism family interviews and reviewing many studies probing germline toxicity of cigarette smoke, is that heavy maternal smoking of the 1950s-70s could be the single greatest contributor to the heritably-driven surge in idiopathic abnormal neurodevelopment we see today. A scientific disconnect may be one reason the autism epidemic remains such a mystery By Jill Escher In 2011, much to my shock and horror, I discovered that as a fetus I had been exposed to regular infusions of potent synthetic steroid hormone drugs deployed as part of a then-popular, if ineffective, anti-miscarriage protocol. Knowing a little bit about the chemical mutilation caused by the fake hormone drug DES (diethylstilbestrol), and a bit about epigenetics as well, I immediately began to question whether my acute exposures—specifically, possible errors they may have induced in my nascent eggs—led to the wildly abnormal neurodevelopmental outcomes in two of my children, both of whom have autism, a "genetic" condition completely without precedent in my or my husbands' families. Shortly after my discovery/hypothesis-conjuring I called my oldest friend to share the news. Her response was immediate: "Josh would have loved this!" By Josh, she was referring to her late stepfather-in-law, the legendary geneticist and Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg. Among his many accomplishments, Lederberg was a leader in developing the field of "environmental mutagenesis." According to Brown University sociologist Scott Frickel, the environmental mutagenesis movement grew out of the revelation that new synthetic and toxic chemicals could have lasting consequences for the human genome, amounting to a future "genetic emergency". Dr. Lederberg was gravely concerned about the possibility the chemical revolution was creating a silent, hidden human genetic emergency that might not be fully realized for decades. As early as 1950, he remarked, "I have the feeling that, in our ignorance, chemical mutagenesis poses a problem of the same magnitude as the indiscriminate use of radiation." (Frickel, Chemical Consequences, p. 51) Five years later, his concerns continued unabated: "more extensive studies are needed to establish, for example, whether the germ cells of man are physiologically insulated against such chemical insults from the environment." (Id.) His colleague James Crow, in "Concern for Environmental Mutagens," summed up their beliefs like this: "The bottom line is human germinal mutation and the translation of this into effects on human welfare. We still have no reliable way to move from DNA damage, however precisely measured, to human well-being n generations from now.... Lowering the mutation rate or preventing its increase is good, even if we don't know how good." (Id. p 135) Decades before I had an inkling about my prenatal chemical exposures—I was probably about 20 at the time and on a trip with my old friend who was soon to marry into his family—I met Dr. Lederberg in his home on the campus of Rockefeller University, where he served as president. Youth is truly wasted on the young because I can only imagine the lively discussion he and I would have today, three decades later. "Why is DNA particularly vulnerable to artificial steroids and their abnormal molecular structures?" "Why is the FDA refusing to require fetal germline effects of pregnancy drugs, and what can be done to change that?" "What is the interplay between epigenetic alterations and predisposition to mutation?" "What components of cigarette smoke might interfere with DNA repair in fetal germ cells?" And the list could go on and on. How regrettable that Dr. Lederberg has passed, because it's my impression that the field of genetics today is largely unconcerned with questions like these. Autism genetics, for example, is focused almost exclusively on gene-hunting with scant curiosity about factors that may have actually caused the wide variety of autism-associated errors in the first place. For the past few months I have been actively pushing a variety of autism cohorts to ascertain grandmaternal smoking habits, and while I've had some success I can't help but sense how completely uninterested nearly all leading autism geneticists are in these sort of questions, questions which strike me as obvious and urgent, given what we know about tobacco-induced mutagenesis and the high rates of maternal smoking in the 1950s-70s. But science has a culture, and presently that culture is divided fairly neatly into scientific silos that tend not to easily intermix. Genetics, mutagenesis, epimutagenesis and chemical/pharmaceutical history tend to be their own worlds. This disconnect may be one of the reasons we're still head-scratching about the colossal surge in autism cases—it seems genetic, but we can't have a "genetic epidemic," right? Or, perhaps, taking a cue from Dr. Lederberg and colleagues, we can. If we're perturbing our germline via novel chemical agents, we most certainly can have a genetic/epigenetic epidemic, what the environmental mutagenesis leaders had called a "genetic emergency" back in the 1960s. It will take a lot more work and creative thinking to probe these questions. I am now a card-carrying member of the Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society, which Dr. Lederberg co-founded in the 1960s, and now work to further scientific investigation into both genetic and epigenetic consequences of exposures. I hope to continually push for multidisciplinary thinking in autism causation, knowing all the while that "Josh would have loved this." Jill Escher is the founder of the Escher Fund for Autism, president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area, and the mother of two children with nonverbal autism. You can learn more about her story here. Links to articles and presentations featuring Jill's story and the germline disruption hypothesis of autism: April 2016, Florida State University Symposium on the Developing Mind keynote: "Out of the Past: Old Exposures, Heritable Effects, and Emerging Concepts for Autism Research." (Slides) November 2015, Bay Area Autism Consortium Conference, "The Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism." (Poster presentation) September 2015, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Conference, "Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism, in a Nutshell." (6-minute video) August 2014, Ancestral Health Symposium: Epigenetics and the Multigenerational Effects of Nutrition, Chemicals and Drugs (40-minute video) November 2013, University of Illinois School of Pharmacy guest lecture, "Are Grandma's Pregnancy Drugs (from the 1950s, 60s and 70s) Partly to Blame for Today's Autism Epidemic?" (Slides) September 2013, Pittsburgh Post Gazette: Can Autism Be Triggered in Future Generations? September 2013, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Conference, Epigenetics Special Interest Group keynote, "20th C. Prenatal Pharmaceuticals & Smoking (& More), Fetal Germline Epigenetics, and Today's Autism Epidemic: Any Connections?" (Slides) August 2013, San Francisco Chronicle: Mother's Quest Could Help Solve Autism Mystery August 2013, Autism Speaks Blog: A Grandmotherly Clue in One Family's Autism Mystery July 2013, Environmental Health News: Onslaught of autism: A mom's crusade could help unravel scientific mystery July 2013, NIH Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee, National Institutes of Health: Autism: Germline Disruption in Personal and Historical Context (15-minute video) March 2013, presentation at the symposium Environmental Epigenetics: New Frontiers in Autism Research (scroll down for 10-minute video) This spring and summer I'll be giving a number of talks on the germline disruption hypothesis of autism and the important role for "citizen science" in improving autism research. You can see the slides from my upcoming talk, "Out of the Past: Old Exposures, Heritable Effects, and Emerging Concepts for Autism Research," April 8 at Florida State University here.

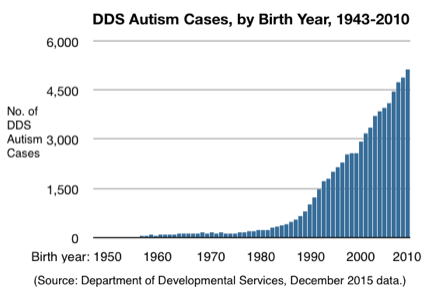

by Jill Escher You’ll have to pardon my tardiness in penning a review of the book NeuroTribes by Steve Silberman. With two autistic children and several jobs, analyzing books that get so much wrong about autism is an endeavor that tends not to top my priority list. But this tome attempting to reinvent the history of autism has unfortunately generated a great deal of interest in some circles, warranting at least some, however belated, response to help correct at least a few of its more grievous errors. But first, let me say something nice. The book is clearly an attempt to create a positive narrative about a disability that has caused tremendous panic and confusion in the public mind. As the mother of cherished children with severe, nonverbal forms of autism, I could not agree more that people disabled by this mysterious condition are a terribly special breed, even if their brains may be short-circuited in some way, or at least not wired for “normal” thinking or behavior. They deserve society’s full respect, acceptance, and support, period. Also, as the book delves into the dark past of how society treated those with cognitive disabilities, it excels in reminding us of when “feebleminded” people even quite a bit less functionally impaired than my children were viewed as “life unworthy of life,” “useless eaters,” or “human ballast,” and routinely mistreated, left to rot in institutions, or worse. It also does a solid job of questioning behavior modification as an autism treatment, and rehashing the history of the disproven vaccine hypothesis of autism. Unfortunately, the book’s welcome elements are overshadowed by its abundant and serious flaws. I’ll discuss just two, but before I do let me offer a brief Cliffs Notes for those who have not read it. NeuroTribes sees autism as a natural condition, a form of neurodiversity harboring both challenges and gifts that is caused solely by age-old genetic variants; it posits that autism rates have not increased over time, but rather the surge is merely an artifact of shifting diagnostic labels, service grabbing, and greater awareness of the post-Rain Man age; it argues that society needs to merely accommodate this somehow formerly hidden mental disability rather than looking for causes or treatments. In order to justify this smiley-faced world view, Silberman serves up heaping platters of misinformation and illogic, as it must to reach such extraordinary conclusions. Let me explain. First, the book relentlessly trivializes autism and the permanent, serious disability it entails by expanding its definition to the ends of he universe. He sees autism is a “strange gift” pervasive in the realm of quirkies and eccentrics, including science fiction fans, university professors, computer programmers, anyone with a prodigious memory, nerds, brainiacs, little professors, math geeks, amateur radio enthusiasts, introverts, and an array of brilliant, enterprising and competent people like scientist Henry Cavendish, inventor Nicola Tesla, inventor Hugo Gernsbach, and a psychiatrist who pioneered his profession’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, among many others. The members of this autistic tribe are uninhibited thinkers who “sketched out a blueprint for the modern networked world,” and “anticipated developments in science.” Before the past two decades or so, these were “Adults wandering in the wilderness with no explanation for their constant struggle” until the definition of autism ostensibly expanded to include them and confer on them a special identity, mode for self-understanding, and rhetorical platform on which to demand therapies and societal accommodations. In defining “autism,” it appears that Silberman and I cannot possibly be talking about the same disorder. I read that “Autistic people are now taking control of their own destinies” while my nonverbal children, with their 30-40ish IQ levels, were shredding my bedsheets, destroying their iPods, shrieking, and jumping around naked. Am I just stupid for somehow missing their hidden ability to control their own destinies and invent modern networking technology? I know hundreds of people with autism, and as much as I adore and value them, almost none of them stand any chance of true independence or controlling their own destinies, let alone attaining stunning achievement in the sciences, or any other discipline for the matter. Yes, I will agree there are some on the mild end who can function fairly independently, but as a hallmark of their disorder often can’t hold a normal conversation, make normal eye contact, make friends, execute solid judgment, negotiate public transportation, fend off abuse, read subtle social cues, vary a routine, and/or hold a job. Even this form of so-called “high-functioning” autism is debilitating, with most individuals needing at least some form of lifelong supervision and support. But for the most part, people with autism are even more incapacitated, such as my friend’s 12 year-old son who regularly attacks his parents and siblings and typically spends his days flicking pieces of string in front of his face. Or my friend’s 18 year-old son who can have a brief conversation but is now 6’ 4” and easily slips into rages involving things like hurling televisions across a room. My friend’s autistic daughter, 17, has some words but cannot attend to her own menstrual periods or personal hygiene, and defecates on her floor. Silberman from time to time touches on these forms of autism, which comprise about half of the spectrum, but usually only to defend the way parents have accepted them instead of trying to change them. Even if clinicians are wildly over-diagnosing mild social impairments as autism, as Silberman contends, there is no evidence in the literature that non-autism diagnostic fakery is driving the increase in diagnosis. Indeed, research shows that only a small fraction of autism cases appear to lose the diagnosis, maybe 7-13% of cases, and even then the subjects are typically left with other serious behavioral or cognitive challenges such as ADHD. Within the walls of clinicians’ offices, autism is no Geek Syndrome, but a markedly impairing pathology that manifests in early development and persists throughout life. The second failure is the book’s breathtakingly confident but absurd conclusion that there’s no true increase in autism. The autism epidemic is nothing more than an “optical illusion” as Silberman stated in a radio interview. In his view, “Asperger’s Lost Tribe” of brainy goofballs populate the bulk of the increase in the autism numbers, with the remainder more impaired cases merely resulting from a shift in labels from “childhood schizophrenia” and “feeblemindedness” to “autism.” While the diagnostics have shifted a bit over the decades, the essential characteristics have not expanded to a “rainbow of a million colors” based on a “veritable banquet of options,” as Silberman puts it. Autism under any regime is a permanent, serious mental disability with criteria based on significant impairments solidly outside the norm of human mental and behavioral development.

When talking about autism growth, it’s fundamental to compare apples to apples, and even among the more classically impaired subset, the numbers have skyrocketed, an area Silberman conveniently omits. For example, as a Californian, it would have been natural and easy for Silberman to have obtained and analyzed our state’s autism data, which is widely regarded as the best in the nation. If he had bothered to look, here’s what he would have found. Since the 1970s, California’s Department of Developmental Services (DDS) has included residents with autism, limited to those deemed developmentally disabled and in need of lifelong care owing to their very significant functional limitations. In other words, it includes only the more severe end of the spectrum, and excludes by definition anything like an “Asperger’s Lost Tribe” of intellectually intact social misfits. Though DDS does not include all people with developmental disability-type autism, as not all families have sought services for their disabled family members, it is generally agreed that the system represents the vast majority of cases, particularly among adults. Notably, DDS autism cases represent only about 59% of same-age autism cases identified through California’s special education system, which employs a broader set of criteria. So, what sort of autism growth has the DDS system seen? Even as DDS has enacted more restrictive eligibility requirements, developmental disability-type autism cases have unequivocally skyrocketed, beginning with births in the early 1980s. DDS now adds about 5,000 autism cases per year, up from about 200 per year just three decades ago. The total DDS autism population now exceeds 83,000 cases, up from about 3,000 25 years ago. And even if one presumes that the system’s mild decline in cases of intellectual disability is due to reallocating those cases to the autism category, this modest shift could not begin to account for the torrential surge in autism cases. Furthermore, to agree with Silberman’s argument, you would have to believe that somehow California’s robust DDS system, regarded as the best and most encompassing in the nation, missed many tens of thousands of cases of one the most incapacitating and obvious mental disorders in the history of humanity. You would have to believe that languishing in attics and basements throughout the state today are tens of thousands of obviously impacted neurodevelopmentally disabled autistic adults who cannot care for themselves but were somehow never picked up by a system designed to find them and serve them. Staff and service providers in our state’s system have been emphatic with me and other community leaders that there is virtually no chance of any appreciable number of DDS-eligible autistic adults, particularly over the age of about 30, not yet identified by our system. DDS-eligible autism cases are even more striking and obvious than mere intellectual disability, and more disabling in their features. There is zero evidence anywhere of a vast horde of DDS-eligible but undetected adults with autism in California. A few years ago when sharing my astonishment about autism epidemic denialism with one of the top officials at DDS, who had worked in the system for decades, he explained that “the people we used to routinely place in institutions were rocket scientists compared to the people coming into the system today.” In other words, people served by the system tended to have milder functional impairments than seen in the glut of autism cases entering the system today. The agency, in a state of shock more than a decade ago when the autism caseload reached a most unexpected 16,000 (laughably small by today’s numbers), erected more stringent, not broader, entry criteria. What’s happening in California, our nation’s most populous state, and the one with the best autism data, is precisely the opposite of what Silberman contends. At an event last week I spoke with the gentleman who first proposed in the 1970s that autism be included in the California DDS system, which in its early decades had been restricted to categories of mental retardation, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy. “People didn’t think it was necessary or of much importance,” said the long-time DDS employee. “There were just so few cases of autism back then.” Silberman would shrug off this gentleman’s observation with the justification that “Autistic people in previous generations were hard to see.” But let me be clear: nothing about developmental disability-type autism, then or now, is or was hard to see. Please come visit DDS autism clients if you think differently. Ask any clinician or teacher if they were just blind to autism back in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. As my 17 year-old son shreds his shirt, and eats sticks, grass and foliage as we hike while tapping furiously at his broken iPod, you tell me that anything about autism is hard to see. As you try to engage with my almost 10 year-old nonverbal daughter in conversation and she doesn’t even seem to notice you are there, tell me again that autism is oh so hard to see. Likewise, it’s striking how the book glances at but then dismisses evidence that autism was once incredibly rare. For example, it acknowledges that Leo Kanner, the nation’s foremost autism expert for decades after he published a seminal paper in 1943, said he had seen only 150 true cases of autism in his entire career, or 8 patients a year, while fielding referrals from as far away as South Africa. Silberman accuses Kanner of artificially restricting autism to a narrow set of severe mental infirmities, denying the right of the Asperger’s Tribe to the same label. But there is no doubt that Kanner would have recognized my nonverbal, food-tossing, paper-shredding kids as autistic, or most of the other 83,000 now in the California DDS system. Silberman states that Autism Society founder Bernie Rimland’s “family pediatrician who had been in practice for 35 years, was at a loss” to diagnose his son Mark, as he had never before seen a case like that. I have found this to be true with every long-time pediatrician with whom I have spoken. It was extremely rare for them to encounter the patently abnormal neurodevelopment of autism — under any label— until roughly the 1990s. But Silberman, always unwavering in this commitment to the idea that the vast majority of autistic children were just hidden behind other labels, implies the entire medical field, including Mark’s ignorant pediatrician, were engaged in sort of mischief around labels instead of noticing truly increasing numbers of cases. Meanwhile, autism has grown to such massive proportions that, at least according to one study out of UC Davis, its burden on the American economy could exceed three percent of GDP in ten years. One mental disorder = 3% GDP. Did you read that? Apart from its discounting of autism data, and our collective historical memories, even more unforgivable is the book’s misleading attempt at a scientific denouement about the always-been-here nature of autism. After its long haul through historical alleyways of questionable relevance it arrives at this statement on page 470: "In recent years, researchers have determined that most cases of autism are not rooted in rare de novo mutations but in very old genes that are shared widely in the general population while being concentrated more in certain families than others. Whatever autism is, it is not a unique product of modern civilization. It is a strange gift from our deep past, passed down through millions of years of evolution." (Emphasis mine.) For this sweepingly confident conclusion, Silberman cites to a single paper, Gaugler et al 2014, “Most genetic risk for autism resides with common variation,” Nat Genet. 2014 Aug; 46(8): 881–885, that speculates, based on statistical methodologies and not direct evidence, that 54% of cases of autism in Sweden may stem from yet-to-be-identified heritable genomic variations. The study did not actually show that the common variations actually caused autism, and did not look at ancestral genetics. And even if you take the study as hard fact, which it is not, it still left 41% of the Swedish autism cases unaccounted for. As always, however, the book skirts or ignores what this very limited study actually says. And worse, the “genes from the deep past” idea is just not true. Evidence is mounting that much of autism is likely attributable to a wide variety of de novo genomic glitches present in the affected children but not their parents. Yuen et al (2015) reported striking findings of heterogenous de novo mutations even among ASD sibling pairs, Iossifov et al (2015) reported that half of autism cases are likely caused by de novo genomic mutations. And just last week Brandler et al found a surprising variety of spontaneous mutations, including simple deletions or insertions and “jumping genes” likely contributing to autism risk. So, are my children’s abnormal brains a “valuable part of humanity’s genetic legacy,” per NeuroTribes, or the result of some intervening factor that damaged the genes from which they are derived? I would strongly argue the latter. If I had to place bets about the heritable source of my children’s strikingly abnormal neurodevelopment I would put all my money on my own (and therefore my vulnerable eggs’ own) 1965 prenatal exposures to extreme doses of synthetic steroid hormones and exactly zilch on the Silbermanian notion of “strange gift from the deep past handed down through millions of years of evolution.” I’ve found innumerable autism parents with similar stories, be it our fetal exposures to pharmaceuticals, drugs, cigarette smoke, or otherwise. This “intergenerational effects” hypothesis is an emerging area of research, with the skewed history of our germ cells finally being put under the proverbial microscope. If you would like to learn more about this hypothesis, please visit my website germlineexposures.org. But enough about developmental biology. Before I close, let me finally highlight the strangeness of the book’s closing paragraph: "With the generation of autistic people diagnosed in the 1990s now coming of age, society can lo longer afford to pretend that autism suddenly loomed up out of nowhere, like the black monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey. There is much work to be done." (Emphasis mine.) Huh? Did I read this correctly? We have a crisis today because we have been pretending that autism barely existed in previous generations? Our autism housing programs, day programs, social services, and schools are pretending they are bursting at the seams with droves of mentally disabled people they never used to see? An entire generation of supremely disabled autistic young adults with nowhere to go, nowhere to live, no one to care for them, because we failed to identify these same supremely disabled people now in their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s? But I guess I should not be surprised at the book's last gasp, since under Silberman’s simplistic and boundless logic, we could have 50%, hey 80%!, of our children flapping, jumping, grunting, nonverbal, and diagnosed autistic today, and they all would necessarily arise from mere shifting views of autism, and we would also necessarily have missed millions of similarly incapacitated adults. To Silberman, there is no other explanation. In closing, NeuroTribes is a phase—some complacency-manifesto-wreckage on the road toward progress in the understanding of this explosion of abnormal neurodevelopment we call autism. While I believe that like many trendy autism mishaps before it, NeuroTribes, too, shall pass, I also fear it may do lasting damage to our society's collective quest for the truth about this extremely serious explosion of brain-based disability. Jill Escher is an autism research philanthropist with the Escher Fund for Autism, a housing provider to adults with developmental disabilities, president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area, and the mother of two children with severe, nonverbal forms of autism. Learn more at jillescher.com. Abundant Pathology in One Family: A Thalidomide Daughter Asks, Where Is the Long-Term Follow Up?2/5/2016 by Michelle Green

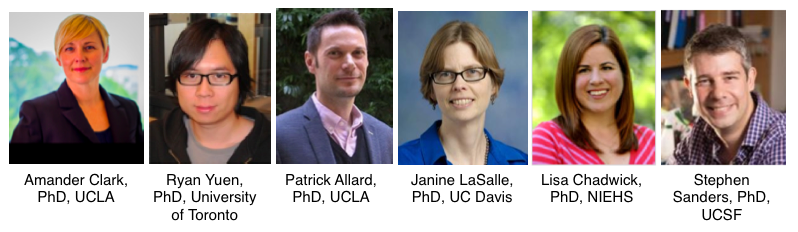

My mother was given thalidomide when she was pregnant with me. I have Hypothyroidism due to Hashimoto's (autoimmune disease). My symptoms can be debilitating and I am not improving with T4 only synthetic hormone. I also have treatment resistant Depressive Illness. My P450 Enzymes are abnormal & I do not respond to medication except at high doses. My peripheral nervous system was damaged causing me pain throughout my body. I am also ADD which was not picked up until I was an adult. My eldest daughter is Dyslexic & has had fertility problems related to Endometriosis. She also suffered several miscarriages before conceiving with IVF. My youngest daughter spent the first week of her life in the Special Care Unit because she would stop breathing & turn blue. She also has hypothyroidism. My son is 'on the spectrum'. He was diagnosed with ASD when he was nine years old. He is intelligent but struggles meeting people & expressing emotion appropriately He is a gifted guitarist. No idea where that came from as he has had no family influence at all. There should of been a follow up on the long term health of ALL children affected by thalidomide, not just the 20% who showed physical damage. No disrespect to those who suffered malformations intended. You have my deepest respect. (This post was submitted to Prenatal Exposures Never Die, a predecessor blog to this one.) On October 1, 2015, the Escher Fund for Autism, Autism Speaks, and the Autism Science Foundation co-sponsored this inaugural online symposium. Attendees included laypeople and researchers from many different fields, but all interested in the intersection between genes, exposures, and disruptions in the instructions that control normal neurodevelopment.

The webinar explored emerging concepts in basic reproductive biology and also the heritability of ASDs. We know that autism is highly heritable, in the sense that ASD risk is higher among siblings, but it's not shown to be highly "genetic" in the classic sense that these traits or genes are passed from generation to generation. To probe what might lie underneath these observations, we felt it important to take a multidisciplinary approach, starting with the complicated biology of germ cells themselves. The unique molecular biology and particular vulnerabilities of the early germline may inform the risk of the "de novo" events we see in autism. By de novo we mean genetic and epigenetic changes arising in the parents' egg or sperm, but not seen in the parents themselves. This effort only scratched the surface of this vast and rapidly developing subject matter, but, we hope it will prompt deeper thinking about autism genetics and inspire further research that may help to connect the dots. Watch the webinar here. by Jeremy Andrews My name is Jeremy, and I have a beautiful nine-year old son, Scotty, who is autistic. This autism seemed to come from nowhere, as I have no autism or similar condition in my family history and neither does my wife, who is from China. Scotty has no identifiable genetic syndrome causing his abnormal neurodevelopment.  Scotty has idiopathic autism. Scotty has idiopathic autism. I come from the UK, and both of my parents were heavy smokers. My father probably came under the definition of a chain-smoker, it was rare to see him without a cigarette in his mouth. My mother smoked 20 cigarettes a day, my father probably 40. My mother didn't give up smoking whilst pregnant with me (although she did for my older brother, I guess it was harder to give up cigarettes by the time I came along). My brother has no biological children. My brother and I never smoked. I always hated the smell of smoke and never tried it even once. I used to use a portable fan to try and blow the second-hand smoke back over the table when playing cards with the family, but it never did much good. One of my strongest memories was going to see "The Towering Inferno" in the cinema and looking around to realize there was more smoke in the auditorium than there was on screen. I don't know with any certainty if my mother's, and my father's, smoking affected my germ cells while I was in gestation. But if the molecular program of my germ cells were damaged by that constant, heavy exposure to tobacco smoke, which contains hundreds of toxic chemicals, perhaps that had a mutagenic or epimutagenic germline effect causing my son's autism. I'd be really interested in finding out, as it seems a very fruitful avenue of research. Jeremy Andrews is a pseudonym for an autism dad who grew up in the UK but now lives in California with his wife and his son, Scotty. by Joanne Wickersham

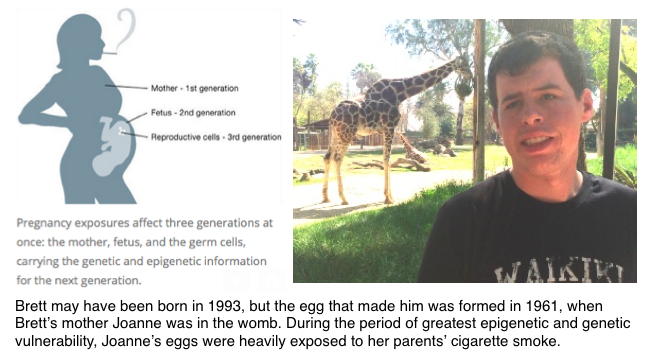

I was born in 1961 in San Jose, California, to a family that has no history of autism, mental disorders, or developmental disorders. My older sister has no children, and I have one, a son born in 1993, named Brett. His early development as a toddler deviated from the norm by 16 months, and at three years old he was diagnosed with autism. He's now a 6'1" 21 year old young man, who is autistic and intellectually disabled (though very sweet and kind) and will need support for his entire life. There were no clear risk factors causing Brett's significant neurodevelopmental disabilities. I am healthy, my ex-husband was healthy. Some years after I had Brett I found out that I had some placental abnormalities that may have caused Brett to be born somewhat small, 5 pounds 6 ounces, but it's unclear if that is sufficient to have caused his significant mental disability. Brett has no genetic disorders or syndromes from what anyone can tell. But I wonder if perhaps he does, in a subtle fashion. I was born in the 1960s when no one thought anything about women smoking in pregnancy. It was not only normal, some doctors advised their pregnant patients to smoke to curb their appetites and keep off weight. My mother was a habitual smoker, smoking a pack a day of Kent cigarettes. She succumbed to lung cancer at age 60. My father was also a heavy, multi-packs-a-day smoker, which meant as a fetus I was also exposed to his second-hand smoke. I cannot help but wonder if my mother's heavy and continuous smoking, every day throughout my gestation, combined with my father's added layer, subtly damaged my eggs, which of course were developing at the time I was in her womb. All those exposures are in a sense "locked into" the eggs, which reprogram and then slip into a sort of hibernation before we are born. Cigarette smoke contains an abundance of toxic chemicals, many of which are known mutagens, and now, known epimutagens. This idea makes sense to me. I encourage the autism research community to investigate the idea that these past exposures that happened when we autism parents were in the womb could have had a toxic generational effect due to germline impacts. The author lives in Silicon Valley. |

AuthorJill Escher, Escher Fund for Autism, is a California-based science philanthropist and mother of two children with severe autism, focused on the question of how environmentally induced germline disruptions may be contributing to today's epidemics of neurodevelopmental impairment. You can read about her discovery of her intensive prenatal exposure to synthetic hormone drugs here. Jill is also president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area. Archives

July 2021

Categories |

- Home

-

Expert Q&A

- Eva Jablonka Q&A

- Amander Clark Q&A

- Mirella Meyer-Ficca Q&A

- Janine LaSalle Q&A

- Dana Dolinoy Q&A

- Ben Laufer Q&A

- Tracy Bale Q&A

- Susan Murphy Q&A

- Alycia Halladay Q&A

- Wendy Chung Q&A

- Pradeep Bhide Q&A

- Pat Hunt Q&A

- Yauk and Marchetti Q&A

- Emilie Rissman Q&A

- Carol Kwiatkowski Q&A

- Linda Birnbaum Q&A

- Virender Rehan Q&A

- Carlos Guerrero-Bosagna Q&A

- Randy Jirtle Q&A

- Jerry Heindel Q&A

- Cheryl Walker Q&A

- Eileen McLaughlin Q&A

- Carmen Marsit Q&A

- Marisa Bartolomei Q&A

- Christopher Gregg Q&A

- Andrea Baccarelli Q&A

- David Moore Q&A

- Patrick Allard Q&A

- Catherine Dulac Q&A

- Lucas Argueso Q&A

- Toshi Shioda Q&A

- Miklos Toth Q&A

- Piroska Szabo Q&A

- Reinisch Q&A

- Klebanoff Q&A

- Denis Noble Q&A

- Germline in the News

- Science

- Presentations

- About Us

- Blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed