A Generation of Drugged DNA?

"I consider the widespread use of obstetric synthetic hormones and other powerful drugs

in the decades after WWII one of the largest toxic spills in history, and one that shot straight into

the bodies of tens of millions of pregnant women, yet almost everyone is oblivious."

Jill Escher is well-known in the autism community for her philanthropy efforts, but the busy California native wears many hats. Not only is she the president of a local autism non-profit and a real estate investor, Escher is also mother to three children — two of whom have nonverbal autism. After receiving her law degree from the University of California, Berkeley, she worked for the U.S. District Court in San Jose before devoting herself full-time to the family fund that she founded with her husband. The Escher Fund for Autism finances a variety of autism research, program and outreach efforts.

As the current president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area, Escher provides a network for autism families to connect and looks for new ways to help adults with autism — for instance, expanding options for support services and affordable, community-based housing. Her most recent project, the resource website Germline Exposures, was created in 2014 as part of her crusade to inform the public about how prenatal exposures can have long-lasting effects on future generations. As someone exposed to synthetic hormones in the womb herself, the cause started as her own personal quest down a rabbit hole of medical records and lab notebooks. Years later, her germline disruption hypothesis has turned into her life's work as she continues to advocate for increased research efforts, an appreciation of the intensity of prenatal pharmaceutical usage in the decades after WWII, as well as stricter drug and chemical risk standards.

Interviewed by Meeri Kim, PhD, March 2014

Tell me a bit about your background. When was the first time you encountered autism?

I consider myself a very typical, normal kid — I was born in 1965 in West Los Angeles. I came from a very typical upper-middle-class, Jewish family with no history of developmental or intellectual disability, mental illness, or the like. Growing up, developmental disability was something I knew precious little about, except that it was something that happened to other people. I had never heard of autism, and I didn't know anybody with autism. Later, I moved to the Bay Area to attend Stanford University, then obtained a law degree from UC-Berkeley. I practiced law for some time — but after having my first autistic child in 1999, I went part-time and eventually left altogether because the demands on my time were so great.

As the current president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area, Escher provides a network for autism families to connect and looks for new ways to help adults with autism — for instance, expanding options for support services and affordable, community-based housing. Her most recent project, the resource website Germline Exposures, was created in 2014 as part of her crusade to inform the public about how prenatal exposures can have long-lasting effects on future generations. As someone exposed to synthetic hormones in the womb herself, the cause started as her own personal quest down a rabbit hole of medical records and lab notebooks. Years later, her germline disruption hypothesis has turned into her life's work as she continues to advocate for increased research efforts, an appreciation of the intensity of prenatal pharmaceutical usage in the decades after WWII, as well as stricter drug and chemical risk standards.

Interviewed by Meeri Kim, PhD, March 2014

Tell me a bit about your background. When was the first time you encountered autism?

I consider myself a very typical, normal kid — I was born in 1965 in West Los Angeles. I came from a very typical upper-middle-class, Jewish family with no history of developmental or intellectual disability, mental illness, or the like. Growing up, developmental disability was something I knew precious little about, except that it was something that happened to other people. I had never heard of autism, and I didn't know anybody with autism. Later, I moved to the Bay Area to attend Stanford University, then obtained a law degree from UC-Berkeley. I practiced law for some time — but after having my first autistic child in 1999, I went part-time and eventually left altogether because the demands on my time were so great.

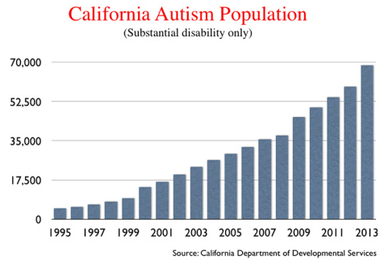

Autism rates in California have skyrocketed.

Autism rates in California have skyrocketed.

Your two autistic children have inspired you to understand its deeper causes. Did they show hints of a developmental disorder very early on?

I have three children, all absolutely gorgeous. My pregnancies were all extremely low risk: normal conceptions, normal gestations with no abnormal exposures, and normal deliveries. No genetic abnormalities. There was no reason to believe that my children, who for all appearances were entirely normal, would have any intellectual difficulties much less something catastrophic — which is what two of them now exhibit.

I had Jonny in 1999, and in retrospect, we should have known something was wrong from the very beginning. He was a very irritable child who didn't make eye contact or respond to his name. He also never pointed or played peekaboo. He didn't meet any of those normal milestones. But again, I didn't even know what autism was back then, so we just thought he was different, and we didn't realize that he had an incapacitating disability. Jonny was officially diagnosed with autism when he was two-and-a-half years old. We suspected that something was wrong with our daughter Sophie, born in 2006, at around 18 months. She didn't develop that normal social reciprocity that you see in babies. She didn't babble, coo, or play normally with toys. But she didn't have all the layers of sensory problems and irritability that Jonathan had. She was a much mellower child than Jonny, and she still is.

Then Sophie was diagnosed with autism as well. What was going through your head at that point?

I just couldn't believe it when Sophie was diagnosed. How in the world could we have ended up with two profoundly disabled children out of seemingly nowhere? It made no sense to me. Just like every other autism parent on the planet, we went through every conceivable possibility of what could have happened to our children. Was it the vaccines? Something I ate or drank? Our ages? We weren't really that old when we had kids, but that's something you hear about a lot. We asked every clinician we could find, and nobody had an answer. What we continued to hear was, “We don't know why your kids have autism, but it seems to be genetic.” But that didn't make sense to us because my husband and I had absolutely no autism, intellectual disability, or mental illness in either of our families. So why this disorder would all of a sudden show up out of nowhere completely mystified us.

On top of that, the autism research world didn't seem to have a huge amount of curiosity about it; they almost gave me like a shoulder-shrugging response: “Oh there's so much autism now, and we don't know why.” People seemed a little complacent. We're talking about kids that are going to cost taxpayers somewhere between $3 and 10 million per child over their lifetime, with maybe one million autistic kids in this country. There seems to be a lack of urgency in the research world that I found just amazing.

Did you suspect at the time that this incidence of autism in your family was part of a larger epidemic?

I had given up trying to figure it out because nothing made sense, yet I saw so much autism in my community that I had never seen when I was growing up. California keeps exceptionally good numbers on the developmentally disabled population, and they were jaw-dropping — they had skyrocketed more than 2000% over 25 years, but nobody had an explanation. Some small portion was perhaps attributable to expansion in diagnosis. But people here in California working with the developmentally disabled didn't believe it because they knew that these kinds of disabilities were always diagnosed as something. I think that there's just this general feeling in the autism world of, “We don't know what hit us.” So I had no hope of ever finding out. I resigned myself to the idea that I would die without ever knowing what happened to my children, and that's just the way it was.

I have three children, all absolutely gorgeous. My pregnancies were all extremely low risk: normal conceptions, normal gestations with no abnormal exposures, and normal deliveries. No genetic abnormalities. There was no reason to believe that my children, who for all appearances were entirely normal, would have any intellectual difficulties much less something catastrophic — which is what two of them now exhibit.

I had Jonny in 1999, and in retrospect, we should have known something was wrong from the very beginning. He was a very irritable child who didn't make eye contact or respond to his name. He also never pointed or played peekaboo. He didn't meet any of those normal milestones. But again, I didn't even know what autism was back then, so we just thought he was different, and we didn't realize that he had an incapacitating disability. Jonny was officially diagnosed with autism when he was two-and-a-half years old. We suspected that something was wrong with our daughter Sophie, born in 2006, at around 18 months. She didn't develop that normal social reciprocity that you see in babies. She didn't babble, coo, or play normally with toys. But she didn't have all the layers of sensory problems and irritability that Jonathan had. She was a much mellower child than Jonny, and she still is.

Then Sophie was diagnosed with autism as well. What was going through your head at that point?

I just couldn't believe it when Sophie was diagnosed. How in the world could we have ended up with two profoundly disabled children out of seemingly nowhere? It made no sense to me. Just like every other autism parent on the planet, we went through every conceivable possibility of what could have happened to our children. Was it the vaccines? Something I ate or drank? Our ages? We weren't really that old when we had kids, but that's something you hear about a lot. We asked every clinician we could find, and nobody had an answer. What we continued to hear was, “We don't know why your kids have autism, but it seems to be genetic.” But that didn't make sense to us because my husband and I had absolutely no autism, intellectual disability, or mental illness in either of our families. So why this disorder would all of a sudden show up out of nowhere completely mystified us.

On top of that, the autism research world didn't seem to have a huge amount of curiosity about it; they almost gave me like a shoulder-shrugging response: “Oh there's so much autism now, and we don't know why.” People seemed a little complacent. We're talking about kids that are going to cost taxpayers somewhere between $3 and 10 million per child over their lifetime, with maybe one million autistic kids in this country. There seems to be a lack of urgency in the research world that I found just amazing.

Did you suspect at the time that this incidence of autism in your family was part of a larger epidemic?

I had given up trying to figure it out because nothing made sense, yet I saw so much autism in my community that I had never seen when I was growing up. California keeps exceptionally good numbers on the developmentally disabled population, and they were jaw-dropping — they had skyrocketed more than 2000% over 25 years, but nobody had an explanation. Some small portion was perhaps attributable to expansion in diagnosis. But people here in California working with the developmentally disabled didn't believe it because they knew that these kinds of disabilities were always diagnosed as something. I think that there's just this general feeling in the autism world of, “We don't know what hit us.” So I had no hope of ever finding out. I resigned myself to the idea that I would die without ever knowing what happened to my children, and that's just the way it was.

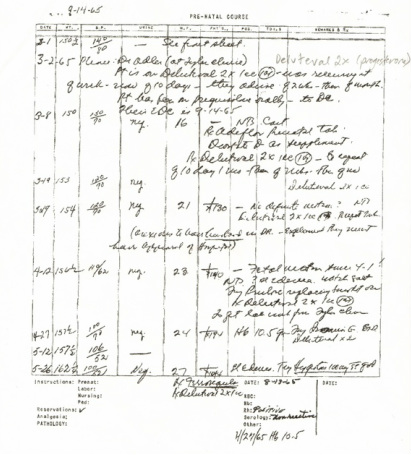

A 1965 medical record reflecting some of Escher's in utero drug exposures.

A 1965 medical record reflecting some of Escher's in utero drug exposures.

Then you fell down a rabbit hole of discovery — after a good amount of investigative work, you found out you were exposed to powerful prenatal drugs while in your mother's womb. How did that all start?

Three-and-a-half years ago, in June 2010, I was reading a newly published study that linked in-vitro fertilization to risk of autism. I had never used any kind of assisted fertility, but a memory popped into my head as I was reading this article. When I was 13 years old, someone, probably my father, pointed to the cover of Time magazine featuring an article about the first test tube baby. He said, “Jill, you were just like this test tube baby — you were a miracle child.” So as that memory wafted through my head, I had the thought that perhaps I had been a some sort of fertility treatment child, though I couldn't imagine what fertility treatments existed in 1965—boy, was I ever ignorant.

I called my mom the next day and asked her if she happened to use fertility treatment with me. She said yes, and I asked, “Do you happen to know what they gave you?” She said, “Oh I don't remember, it was so long ago; they gave me a whole bunch of stuff.” Her fertility clinic was still in business in West Los Angeles — it was a very pioneering, popular fertility clinic in the 60s — but they had nothing. All their records were gone. Then my mom called her obstetrician, who was the successor to her original OB in the 1960s, and thankfully that office had some of her medical records on microfilm from 1965.

It turns out that the fertility doctor had given her some ovulation-inducing drugs, Clomiphene and Pergonal, as part of her treatment, but there was also a whole bunch of other writing that was difficult to decipher. So I put the papers away and pretty much forgot about them. During the following year I developed a really intense interest in the science and policy of nutrition, and in October 2011 listened to a nutrition podcast in which the food guru said what a mother eats during pregnancy affects not only her fetus, but also her grandchildren because those germ cells form within the fetus during gestation. All of a sudden this light bulb went off in my head — maybe I had been exposed to a drug that affected the development of my eggs, and therefore my children.

Three-and-a-half years ago, in June 2010, I was reading a newly published study that linked in-vitro fertilization to risk of autism. I had never used any kind of assisted fertility, but a memory popped into my head as I was reading this article. When I was 13 years old, someone, probably my father, pointed to the cover of Time magazine featuring an article about the first test tube baby. He said, “Jill, you were just like this test tube baby — you were a miracle child.” So as that memory wafted through my head, I had the thought that perhaps I had been a some sort of fertility treatment child, though I couldn't imagine what fertility treatments existed in 1965—boy, was I ever ignorant.

I called my mom the next day and asked her if she happened to use fertility treatment with me. She said yes, and I asked, “Do you happen to know what they gave you?” She said, “Oh I don't remember, it was so long ago; they gave me a whole bunch of stuff.” Her fertility clinic was still in business in West Los Angeles — it was a very pioneering, popular fertility clinic in the 60s — but they had nothing. All their records were gone. Then my mom called her obstetrician, who was the successor to her original OB in the 1960s, and thankfully that office had some of her medical records on microfilm from 1965.

It turns out that the fertility doctor had given her some ovulation-inducing drugs, Clomiphene and Pergonal, as part of her treatment, but there was also a whole bunch of other writing that was difficult to decipher. So I put the papers away and pretty much forgot about them. During the following year I developed a really intense interest in the science and policy of nutrition, and in October 2011 listened to a nutrition podcast in which the food guru said what a mother eats during pregnancy affects not only her fetus, but also her grandchildren because those germ cells form within the fetus during gestation. All of a sudden this light bulb went off in my head — maybe I had been exposed to a drug that affected the development of my eggs, and therefore my children.

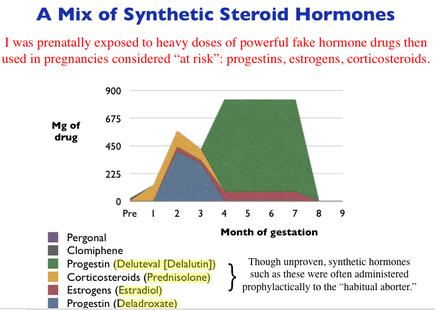

Escher was prenatally exposed to a soup of synthetic hormone drugs.

Escher was prenatally exposed to a soup of synthetic hormone drugs.

So then you felt motivated to dig up those old records again?

Yes, and this time I tried harder to decipher them. One word kept popping up on one of the medical records, and it ended up being a drug called Deluteval. Clearly, my mother had been given this drug repeatedly during my gestation. When I typed “Deluteval” into Google Scholar, a study came up published in 1977 called “Prenatal Exposure to Synthetic Progestins and Estrogens: Effects on Human Development.” It was written by a woman named June Reinisch and another author named William Karow.

Dr. Reinisch realized that doctors were prolifically giving pregnant women synthetic hormones for a whole host of reasons, and she wondered about the drugs' effects on the fetus — which, in the 60's and 70's, was an idea that was dismissed by the medical community that still considered the placenta a barrier to harm, in fact they called it "the placental barrier." Doctors felt that women with pregnancy complications — it could have been spotting, or twins, or diabetes, or small frame — would somehow be protected by excess hormones. But most frequently, these drug protocols were administered to women like my mom who had suffered prior miscarriages — they were labeled "habitual aborters" back then by their doctors, who were taught they should supplement hormone levels in some fashion, especially with synthetic progestins. The drug companies pedalled these drugs hard, and nobody really questioned it.

Deluteval, a synthetic progestin, was one of several progestin drugs popular at the time. In that 1977 paper, Dr. Reinisch focused on children who were exposed to various synthetic hormone drugs including progestins, estrogens, and corticosteroids — along with their unexposed siblings who were used as controls — to find any effects on personality or intellectual development.

I read that paper and almost died: I realized that I had been one of the 71 subjects studied. I remember the researchers coming to my house when I was 8 years old and interviewing me, giving me IQ tests, playing with me. Another clue was hidden in my mother's microfiche file: a letter written to the doctor by June Reinisch. Funnily enough, I tracked her down in 2012 and she is now one of my dear friends, and this was her Ph.D project. She found no difference in IQ, but she did find distinct differences in our personalities, though she didn't use the term, we were more "Aspie," than our unexposed siblings — less groupish, more independent, less emotionally attached.

Steroid hormones are powerful little molecules that do their job by entering the cell nucleus and changing gene expression. Synthetic steroid hormones are lab-made molecules not found in nature that mimic effects of natural hormones but are shaped differently and operate differently on a molecular level. It occurred to me that synthetic steroids' epigenetic (referring to molecular control of gene expression) effects on a developing germline could be profound.

Yes, and this time I tried harder to decipher them. One word kept popping up on one of the medical records, and it ended up being a drug called Deluteval. Clearly, my mother had been given this drug repeatedly during my gestation. When I typed “Deluteval” into Google Scholar, a study came up published in 1977 called “Prenatal Exposure to Synthetic Progestins and Estrogens: Effects on Human Development.” It was written by a woman named June Reinisch and another author named William Karow.

Dr. Reinisch realized that doctors were prolifically giving pregnant women synthetic hormones for a whole host of reasons, and she wondered about the drugs' effects on the fetus — which, in the 60's and 70's, was an idea that was dismissed by the medical community that still considered the placenta a barrier to harm, in fact they called it "the placental barrier." Doctors felt that women with pregnancy complications — it could have been spotting, or twins, or diabetes, or small frame — would somehow be protected by excess hormones. But most frequently, these drug protocols were administered to women like my mom who had suffered prior miscarriages — they were labeled "habitual aborters" back then by their doctors, who were taught they should supplement hormone levels in some fashion, especially with synthetic progestins. The drug companies pedalled these drugs hard, and nobody really questioned it.

Deluteval, a synthetic progestin, was one of several progestin drugs popular at the time. In that 1977 paper, Dr. Reinisch focused on children who were exposed to various synthetic hormone drugs including progestins, estrogens, and corticosteroids — along with their unexposed siblings who were used as controls — to find any effects on personality or intellectual development.

I read that paper and almost died: I realized that I had been one of the 71 subjects studied. I remember the researchers coming to my house when I was 8 years old and interviewing me, giving me IQ tests, playing with me. Another clue was hidden in my mother's microfiche file: a letter written to the doctor by June Reinisch. Funnily enough, I tracked her down in 2012 and she is now one of my dear friends, and this was her Ph.D project. She found no difference in IQ, but she did find distinct differences in our personalities, though she didn't use the term, we were more "Aspie," than our unexposed siblings — less groupish, more independent, less emotionally attached.

Steroid hormones are powerful little molecules that do their job by entering the cell nucleus and changing gene expression. Synthetic steroid hormones are lab-made molecules not found in nature that mimic effects of natural hormones but are shaped differently and operate differently on a molecular level. It occurred to me that synthetic steroids' epigenetic (referring to molecular control of gene expression) effects on a developing germline could be profound.

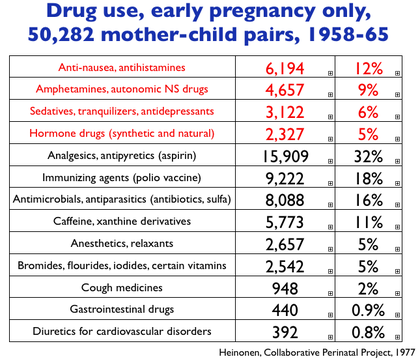

Snapshot of 1st trimester prenatal drugs in the early 1960s.

Snapshot of 1st trimester prenatal drugs in the early 1960s.

That is a remarkable coincidence! Did you feel relieved at that point because you had found a potential explanation?

The incredible shock that I felt upon realizing what very likely happened to me and my children was so intense that I went into a profound state of despair that literally almost killed me. It was just an unforgettable moment. Dr. Reinisch, who went on to become director of the famed Kinsey Institute from 1982-1993, saved all the dosage records, and I finally confirmed that I had been exposed to very heavy and continual doses these powerful drugs in utero — coinciding with the time when my eggs developed, within the first five months of gestation. It was roughly equivalent to 30,000 of today's birth control pills. Just imagine that! And this medical practice was not uncommon at the time!

Even more shocking than that tens of millions of us born in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s were heavily exposed to these powerful endocrine-disrupting drugs, is that almost nobody knows about it. I consider the widespread use of obstetric synthetic hormones and other powerful drugs in the decades after WWII one of the largest toxic spills in history, and one that shot straight into the bodies of tens of millions of pregnant women, yet almost everyone is oblivious. We cannot understand the autism epidemic unless we first grasp this forgotten chapter in medical practice and human biological history.

Have you met many other autism families with a similar history to yours?

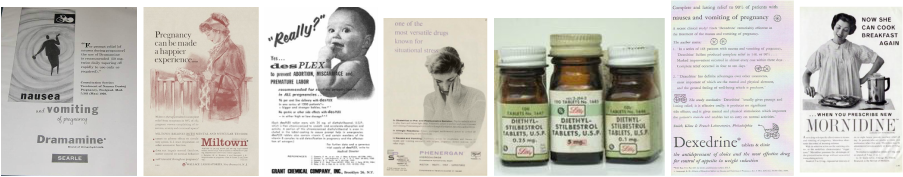

Oh, many, many! Though for the most part people have absolutely not the foggiest idea what they were exposed to in the womb. But what to me is most telling is that in the group of peers who knew of their drug exposures, their unexposed siblings tended to have typically developing kids. I talk to autism parents of my generation all the time, and they tell me stories of all kinds of stuff they were exposed to: anti-miscarriage drugs, or anti-nausea drugs, sedatives, psychoactive drugs, smoking. I'm very suspicious that these drugs had endocrine-disrupting properties just as synthetic hormones overtly exhibit. At this point, no one has directly studied which drugs will have germline effects on humans, but based on animal models and our understanding of epigenetic mechanisms, if they have endocrine disrupting properties, then they are likely to have some kind of adverse germline effect.

This autism epidemic that we have today has all of nothing to do with better ascertainment. What we have today is an actual explosion in the population of people under the age of about 25 who have substantial neurodevelopmental disability. This population did not exist before. The timeline of the germline disruption theory does scale perfectly with the timing of the autism explosion — but do I think that its the only contributing factor to the autism epidemic? Absolutely not, and hopefully in the next few years we'll get some more clues from the research.

The incredible shock that I felt upon realizing what very likely happened to me and my children was so intense that I went into a profound state of despair that literally almost killed me. It was just an unforgettable moment. Dr. Reinisch, who went on to become director of the famed Kinsey Institute from 1982-1993, saved all the dosage records, and I finally confirmed that I had been exposed to very heavy and continual doses these powerful drugs in utero — coinciding with the time when my eggs developed, within the first five months of gestation. It was roughly equivalent to 30,000 of today's birth control pills. Just imagine that! And this medical practice was not uncommon at the time!

Even more shocking than that tens of millions of us born in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s were heavily exposed to these powerful endocrine-disrupting drugs, is that almost nobody knows about it. I consider the widespread use of obstetric synthetic hormones and other powerful drugs in the decades after WWII one of the largest toxic spills in history, and one that shot straight into the bodies of tens of millions of pregnant women, yet almost everyone is oblivious. We cannot understand the autism epidemic unless we first grasp this forgotten chapter in medical practice and human biological history.

Have you met many other autism families with a similar history to yours?

Oh, many, many! Though for the most part people have absolutely not the foggiest idea what they were exposed to in the womb. But what to me is most telling is that in the group of peers who knew of their drug exposures, their unexposed siblings tended to have typically developing kids. I talk to autism parents of my generation all the time, and they tell me stories of all kinds of stuff they were exposed to: anti-miscarriage drugs, or anti-nausea drugs, sedatives, psychoactive drugs, smoking. I'm very suspicious that these drugs had endocrine-disrupting properties just as synthetic hormones overtly exhibit. At this point, no one has directly studied which drugs will have germline effects on humans, but based on animal models and our understanding of epigenetic mechanisms, if they have endocrine disrupting properties, then they are likely to have some kind of adverse germline effect.

This autism epidemic that we have today has all of nothing to do with better ascertainment. What we have today is an actual explosion in the population of people under the age of about 25 who have substantial neurodevelopmental disability. This population did not exist before. The timeline of the germline disruption theory does scale perfectly with the timing of the autism explosion — but do I think that its the only contributing factor to the autism epidemic? Absolutely not, and hopefully in the next few years we'll get some more clues from the research.

What sorts of research efforts has the Escher Fund for Autism financed?

From my dozens of conversations with researchers after finding out about my exposures, I came to the conclusion that the most important thing to do was to try to get some human epidemiological studies going. The first study that we developed was with Dr. Reinisch herself, who suggested we study grandoffspring of a large cohort of women in Denmark who were exposed to various drugs during pregnancy in 1960. She was retired and living in Brooklyn, but still actively engaged in research. Denmark has excellent medical and prescription records, and it is much easier to trace the grandchildren and characterize their diagnoses. The research team is looking for associations between abnormal developmental outcomes in grandchildren and those 1960 fetal germline exposures. We also have a preliminary study based on the cohort here in California that is just getting underway, and there are two others that are good candidate cohorts located back East. We recently issued an RFP to spur more research, and have helped sponsor conferences on epigenetics.

Do you feel that there's still some complacency in the research or regulatory world regarding germline effects?

Some complacency? Almost complete complacency. Part of that is this long-standing, very stagnant paradigm that has really weighed down autism research that pins down the cause as either genes or environment. That continues to be the dominant paradigm in autism research. You're either looking for genes, or you're looking for some kind of environmental perturbation that affected early brain development. But I think much of it is this combination of induced genetic disruption, and that's where the autism world has not looked.

They did look in one respect — advanced maternal and paternal age — but unfortunately, autism academia has not fully caught up to the notion that evolution is much, much more complex than random mutation. In fact, environmental influence bears very heavily on what happens to the germline in all organisms.

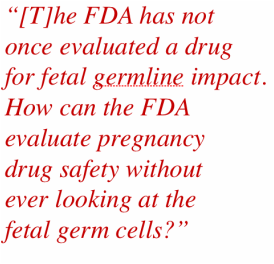

Regarding regulatory agencies, the FDA has not once evaluated a drug for fetal germline impact. How can the FDA evaluate pregnancy drug safety without ever looking at the fetal germ cells, the most important cells in a baby's body? I've petitioned the FDA to do this sort of safety assessment, and they haven't responded. Maybe we don't exactly know the minutiae of every molecular mechanism , but science clearly shows us that there could be a risk to the germline with certain drugs. We cannot characterize that risk quite yet, but we know these cells are vulnerable based on animal models. The FDA should tell pregnant women before they pop, say, an antidepressant, that doing so may affect your grandchildren.

Links to articles and presentations featuring Jill's story and the Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism:

September 2019, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: Heritable Impacts of Toxicant Exposures: A Gap in Research and Regulation. (YouTube video, plus article in NIEHS Environmental Factor)

September 2019, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society conference: Research and Regulatory Implications of Germline Vulnerabilities to Drugs and Chemicals. (YouTube video)

September 2019, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Heritable Hazards of Smoking Workshop. (YouTube video playlist)

August 2019, Epigenetic Inheritance Symposium. "Heritable Impacts of General Anesthesia." (YouTube video)

July 2019, Society for the Study of Reproduction, San Jose; and Gordon Research Conference on Epigenetics, New Hampshire. "Investigating the Heritable Impacts of Germ Cell Toxicant Exposures" (poster PDF)

June 2019, Brazilian Mutagenesis Conference. "Germ Cell Toxicant Exposures: A Gap in Research and Regulation." (YouTube video)

January 2019, Bay Area Autism Consortium conference, poster, "Investigating the Missing Heritability of Autism." (PDF)

September 2017, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society conference, Raleigh, Grandmaternal Pregnancy Smoking and Autism Outcomes in Grandoffspring (slides)

August 2017, Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Implications for Biology and Society conference, Zurich, Investigating Germ Cell Exposures and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes (video)

February 2017, Autism in the Family Conference, Santa Rosa, What Does the Future Hold for Autism Families? (slides)

February 2017, Society for Neuroscience Wonder symposium: "Time Bomb: A Journey into Old Exposures, Gamete Glitches, and the Autism Explosion"

July 2016, Autism Society of America Conference: "The Importance of Citizen Science in Autism Research" (slides)

April 2016, Florida State University Symposium on the Developing Mind keynote: "Out of the Past: Old Exposures, Heritable Effects, and Emerging Concepts for Autism Research." (Video and Slides)

November 2015, Bay Area Autism Consortium Conference, "The Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism." (Poster presentation)

September 2015, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Conference, "Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism, in a Nutshell." (6-minute video)

August 2014, Ancestral Health Symposium: Epigenetics and the Multigenerational Effects of Nutrition, Chemicals and Drugs (40-minute video)

November 2013, University of Illinois School of Pharmacy guest lecture, "Are Grandma's Pregnancy Drugs (from the 1950s, 60s and 70s) Partly to Blame for Today's Autism Epidemic?" (Slides)

September 2013, Pittsburgh Post Gazette: Can Autism Be Triggered in Future Generations?

September 2013, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Conference, Epigenetics Special Interest Group keynote, "20th C. Prenatal Pharmaceuticals & Smoking (& More), Fetal Germline Epigenetics, and Today's Autism Epidemic: Any Connections?" (Slides)

August 2013, San Francisco Chronicle: Mother's Quest Could Help Solve Autism Mystery

August 2013, Autism Speaks Blog: A Grandmotherly Clue in One Family's Autism Mystery

July 2013, Environmental Health News: Onslaught of autism: A mom's crusade could help unravel scientific mystery

July 2013, NIH Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee, National Institutes of Health: Autism: Germline Disruption in Personal and Historical Context (15-minute video)

March 2013, presentation at the symposium Environmental Epigenetics: New Frontiers in Autism Research (scroll down for 10-minute video)

From my dozens of conversations with researchers after finding out about my exposures, I came to the conclusion that the most important thing to do was to try to get some human epidemiological studies going. The first study that we developed was with Dr. Reinisch herself, who suggested we study grandoffspring of a large cohort of women in Denmark who were exposed to various drugs during pregnancy in 1960. She was retired and living in Brooklyn, but still actively engaged in research. Denmark has excellent medical and prescription records, and it is much easier to trace the grandchildren and characterize their diagnoses. The research team is looking for associations between abnormal developmental outcomes in grandchildren and those 1960 fetal germline exposures. We also have a preliminary study based on the cohort here in California that is just getting underway, and there are two others that are good candidate cohorts located back East. We recently issued an RFP to spur more research, and have helped sponsor conferences on epigenetics.

Do you feel that there's still some complacency in the research or regulatory world regarding germline effects?

Some complacency? Almost complete complacency. Part of that is this long-standing, very stagnant paradigm that has really weighed down autism research that pins down the cause as either genes or environment. That continues to be the dominant paradigm in autism research. You're either looking for genes, or you're looking for some kind of environmental perturbation that affected early brain development. But I think much of it is this combination of induced genetic disruption, and that's where the autism world has not looked.

They did look in one respect — advanced maternal and paternal age — but unfortunately, autism academia has not fully caught up to the notion that evolution is much, much more complex than random mutation. In fact, environmental influence bears very heavily on what happens to the germline in all organisms.

Regarding regulatory agencies, the FDA has not once evaluated a drug for fetal germline impact. How can the FDA evaluate pregnancy drug safety without ever looking at the fetal germ cells, the most important cells in a baby's body? I've petitioned the FDA to do this sort of safety assessment, and they haven't responded. Maybe we don't exactly know the minutiae of every molecular mechanism , but science clearly shows us that there could be a risk to the germline with certain drugs. We cannot characterize that risk quite yet, but we know these cells are vulnerable based on animal models. The FDA should tell pregnant women before they pop, say, an antidepressant, that doing so may affect your grandchildren.

Links to articles and presentations featuring Jill's story and the Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism:

September 2019, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: Heritable Impacts of Toxicant Exposures: A Gap in Research and Regulation. (YouTube video, plus article in NIEHS Environmental Factor)

September 2019, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society conference: Research and Regulatory Implications of Germline Vulnerabilities to Drugs and Chemicals. (YouTube video)

September 2019, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Heritable Hazards of Smoking Workshop. (YouTube video playlist)

August 2019, Epigenetic Inheritance Symposium. "Heritable Impacts of General Anesthesia." (YouTube video)

July 2019, Society for the Study of Reproduction, San Jose; and Gordon Research Conference on Epigenetics, New Hampshire. "Investigating the Heritable Impacts of Germ Cell Toxicant Exposures" (poster PDF)

June 2019, Brazilian Mutagenesis Conference. "Germ Cell Toxicant Exposures: A Gap in Research and Regulation." (YouTube video)

January 2019, Bay Area Autism Consortium conference, poster, "Investigating the Missing Heritability of Autism." (PDF)

September 2017, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society conference, Raleigh, Grandmaternal Pregnancy Smoking and Autism Outcomes in Grandoffspring (slides)

August 2017, Transgenerational Epigenetic Inheritance: Implications for Biology and Society conference, Zurich, Investigating Germ Cell Exposures and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes (video)

February 2017, Autism in the Family Conference, Santa Rosa, What Does the Future Hold for Autism Families? (slides)

February 2017, Society for Neuroscience Wonder symposium: "Time Bomb: A Journey into Old Exposures, Gamete Glitches, and the Autism Explosion"

July 2016, Autism Society of America Conference: "The Importance of Citizen Science in Autism Research" (slides)

April 2016, Florida State University Symposium on the Developing Mind keynote: "Out of the Past: Old Exposures, Heritable Effects, and Emerging Concepts for Autism Research." (Video and Slides)

November 2015, Bay Area Autism Consortium Conference, "The Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism." (Poster presentation)

September 2015, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Conference, "Germline Disruption Hypothesis of Autism, in a Nutshell." (6-minute video)

August 2014, Ancestral Health Symposium: Epigenetics and the Multigenerational Effects of Nutrition, Chemicals and Drugs (40-minute video)

November 2013, University of Illinois School of Pharmacy guest lecture, "Are Grandma's Pregnancy Drugs (from the 1950s, 60s and 70s) Partly to Blame for Today's Autism Epidemic?" (Slides)

September 2013, Pittsburgh Post Gazette: Can Autism Be Triggered in Future Generations?

September 2013, Environmental Mutagenesis and Genomics Society Conference, Epigenetics Special Interest Group keynote, "20th C. Prenatal Pharmaceuticals & Smoking (& More), Fetal Germline Epigenetics, and Today's Autism Epidemic: Any Connections?" (Slides)

August 2013, San Francisco Chronicle: Mother's Quest Could Help Solve Autism Mystery

August 2013, Autism Speaks Blog: A Grandmotherly Clue in One Family's Autism Mystery

July 2013, Environmental Health News: Onslaught of autism: A mom's crusade could help unravel scientific mystery

July 2013, NIH Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee, National Institutes of Health: Autism: Germline Disruption in Personal and Historical Context (15-minute video)

March 2013, presentation at the symposium Environmental Epigenetics: New Frontiers in Autism Research (scroll down for 10-minute video)