|

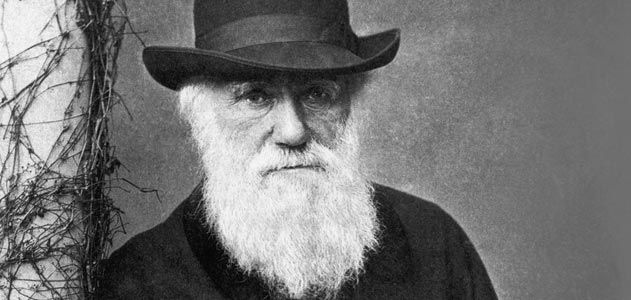

The idea of “conditions of life” affecting germ cells is so old-school it can be traced back to The Origin of Species in 1859 "I believe that the conditions of life, from their action on the reproductive system, are so far of the highest importance as causing variability,” wrote Darwin 159 years ago. By Jill Escher

The TwitterSphere has been crackling lately with heated debate about epigenetic inheritance—is it a Thing? Is it distracting Lamarckian, anti-Darwinian nonsense? Does it even matter for science or human health? Being firmly on the side of yaaaaaasss, intergenerational epigenetic inheritance is for sure a Thing, and really super important Thing for humans and other beasts at that, I got my share of virtual eye rolls for holding such a “radical” idea. In the opposite corner of the ring was Kevin Mitchell, who has made a name for himself as an entrenched skeptic of both intergenerational (involving a direct germline stressor) and transgenerational inheritance (involving no direct germ cell exposure). In recent blogs (here and here) he insisted the scientific literature was devoid of convincing evidence of even intergenerational epigenetic inheritance in mammals or humans (which I pointed out, citing an abundance of studies, was egregious overstatement, here). Shaken by his dogmatism and hyperbole, I shed a little tear and consoled myself in the pages of pretty good book, called The Origin of Species, by my one of favorite guys, Charles Darwin. Darwin’s theory of evolution has often been summed up as “random mutation and natural selection,” but anyone who has read Origin must be aware, Darwin’s views on the source of variation had little to do with randomness (or with mutations, as he was not remotely aware of DNA or genes). Darwin puzzled over the forces behind variation and admitted he lacked a clear answer, but he insisted he was “strongly inclined” toward the existence of a certain phenomenon, which he addressed multiple times in Origin. What phenomenon? Well, it’s something strikingly consistent with the idea of intergenerational epigenetic inheritance. Darwin introduces the concept in Chapter 1, Variation under Domestication. He writes that while variability may be induced by exposures to the embryo, “I am strongly inclined to suspect that the most frequent cause of variability may be attributed to the male and female reproductive elements having been affected prior to the act of conception.” (The Origin of Species, p. 10) In other words, Darwin thinks some experiences of the sperm and egg at some point(s) before conception, generate variation in how they are expressed. He then explains his chief reason for suspecting this is his observation in domestic animals that the reproductive system appears “to be far more susceptible than any other part of the organization, to the action of any change in the conditions of life.” (Id. 11) In plants he notes that “trifling changes, such as a little more or less water at some particular period of growth, will determine whether or not the plant sets a seed.” (Id.) He then explain that plant sports, which he sees as common under cultivation, support his view “that variability may be largely attributed to the ovules or pollen, or to both, having been affected by the treatment of the parent prior to the act of conception.” (Id. 12) He goes on to argue against direct (what we today would call prenatal somatic) exposures as having much influence over variability in animals, though he sees more such influence in plants. (Id. 12-13) Lest you think his musings on germline exposures (to use today’s language) generating variation in offspring are a fluke, please consider how often he returns to this theme. After stating that the continual breeding of horses, cattle and poultry for an “almost infinite number of generations” is obviously possible based on society’s long experience of domestication, he adds “that when under nature the conditions of life do change, variations and reversions of character probably do occur; but natural selection, as will hereafter be explained, will determine how far the new characters thus arising shall be preserved. (Id. 17) In other words, environmental context in nature can probably drive development of variations, on which natural selection then acts. Darwin closes Chapter 1 with a summary, reiterating, “I believe that the conditions of life, from their action on the reproductive system, are so far of the highest importance as causing variability,” then he admits “variability is governed by many unknown laws, with “the final result is thus rendered infinitely complex.” (Id. 44) Now let’s move on to Chapter 5, “Laws of Variation.” He starts off by dismissing the idea of “chance” as the force generating variation in offspring. He says “I have hitherto sometimes spoken as if the variations so common and multiform in organic beings under domestication, and in a lesser degree in those in a state of nature--had been due to chance. This, of course, is a wholly incorrect expression, but it serves to acknowledge plainly our ignorance of the cause of each particular variation.” (Id. 133) He asserts the greater force in creating variability, as well as “monstrosities” under domestication or cultivation, “are in some way due to the nature of the conditions of life, to which the parents and their more remote ancestors have been exposed during several generations.” Oh dear, that's transgenerational, or at least cumulative-generational, inheritance— this man was truly a hypothesis-maker way ahead of his time (hat tip here to Pat Hunt's recent study, Horan TS, et al. Germline and reproductive tract effects intensify in male mice with successive generations of estrogenic exposure. PLOS Genetics 2017;1006885). He repeats that the “reproductive system is eminently susceptible to changes in the conditions of life; and to this system being functionally disturbed in the parents, I chiefly attribute the varying or plastic condition of the offspring.” (Id. 133-34) I nearly fainted when I read that last sentence. With joy, with relief, with sheer worshipfulness of Mr. Darwin. This sums up my work, my hypothesis, my life story. While I won’t go into the details here you can read them in Bugs in the Program, published in the journal Environmental Epigenetics. In short, I contend my early “reproductive system’s” (germ cells) heavy prenatal exposure to a bizarre “condition of life” (huge doses of synthetic steroid hormone drugs) caused the “varying condition” of my offspring (dysregulated neurodevelopment). It appears this game of connect-the-dots would not have fazed Mr. Darwin at all. And, to further cheer me up, I guess, he then emphasizes it again: "The male and female sexual elements seem to be affected before that union takes place which is to form a new being…. we may feel sure that there must be some cause for each deviation of structure, however slight.” (Id. 134) Then, he again dismisses the idea of proximate somatic exposures having much effect. “How much direct effect difference of climate, food, &c., produces on any being is extremely doubtful.” The totality of traits results from some mix “accumulative action of natural selection” and “conditions of life.” (Id. 135) But he is pretty certain that “conditions of life" must be acting “indirectly,” by which he means “affecting the reproductive system, and in thus inducing variability.” After that, "natural selection will then accumulate all profitable variations, however slight, until they become plainly developed and appreciable by us.” (Idd 136) Toward the close of the book, Darwin reiterates the causes of variation act indirectly, through conditions affecting the parental reproductive elements. The cause of variation “I believe generally has acted, even before the embryo is formed; and the variation may be due to the male and female sexual elements having been affected by the conditions to which either parent, or their ancestors, have been exposed." (Id. 433-434) Darwin could not possibly have been more prescient when he wrote in his final pages, “A grand and almost untrodden field of inquiry will be opened, on the causes and laws of variation, on correlation, on the effects of use and disuse, on the direct action of external conditions, and so forth.” (Id. 474) For decades, however, science has been tragically stuck in the rut of “random mutation” as the cause of variation, and a rigid sort of genetic determinism, in clear contravention of Darwin’s own views. It's only now that this untrodden field is finally opening to its true breadth. One further note: Several years after publishing The Origin of Species, Darwin further hypothesized that tiny "gemmules" took information from the body to the germ cells, influencing traits of offspring. We now know of transfer of various forms of somatic molecular information to germ cells via cytoplasmic bridges. Two more points for Chuck. I hope my work can play a small part in the flowering of Darwin’s original ideas about exposures to the parental germ cells influencing traits in offspring. Today there is little doubt the germline epigenome, as influenced by exposures to the germ cells, can actively play a role in determining gene expression, and thus traits, in the resulting organism. To this, Darwin would not say "What a radical idea!" but rather, “Of course, I've been saying that for 159 years!” [All emphasis, mine.] Source: Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882. On The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Original text of first ed London:John Murray, 1859. In mass market reissue, New York:Bantam Classic, 2008. Jill Escher is a research philanthropist. Learn more at GermlineExposures.org.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJill Escher, Escher Fund for Autism, is a California-based science philanthropist and mother of two children with severe autism, focused on the question of how environmentally induced germline disruptions may be contributing to today's epidemics of neurodevelopmental impairment. You can read about her discovery of her intensive prenatal exposure to synthetic hormone drugs here. Jill is also president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area. Archives

July 2021

Categories |

- Home

-

Expert Q&A

- Eva Jablonka Q&A

- Amander Clark Q&A

- Mirella Meyer-Ficca Q&A

- Janine LaSalle Q&A

- Dana Dolinoy Q&A

- Ben Laufer Q&A

- Tracy Bale Q&A

- Susan Murphy Q&A

- Alycia Halladay Q&A

- Wendy Chung Q&A

- Pradeep Bhide Q&A

- Pat Hunt Q&A

- Yauk and Marchetti Q&A

- Emilie Rissman Q&A

- Carol Kwiatkowski Q&A

- Linda Birnbaum Q&A

- Virender Rehan Q&A

- Carlos Guerrero-Bosagna Q&A

- Randy Jirtle Q&A

- Jerry Heindel Q&A

- Cheryl Walker Q&A

- Eileen McLaughlin Q&A

- Carmen Marsit Q&A

- Marisa Bartolomei Q&A

- Christopher Gregg Q&A

- Andrea Baccarelli Q&A

- David Moore Q&A

- Patrick Allard Q&A

- Catherine Dulac Q&A

- Lucas Argueso Q&A

- Toshi Shioda Q&A

- Miklos Toth Q&A

- Piroska Szabo Q&A

- Reinisch Q&A

- Klebanoff Q&A

- Denis Noble Q&A

- Germline in the News

- Science

- Presentations

- About Us

- Blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed