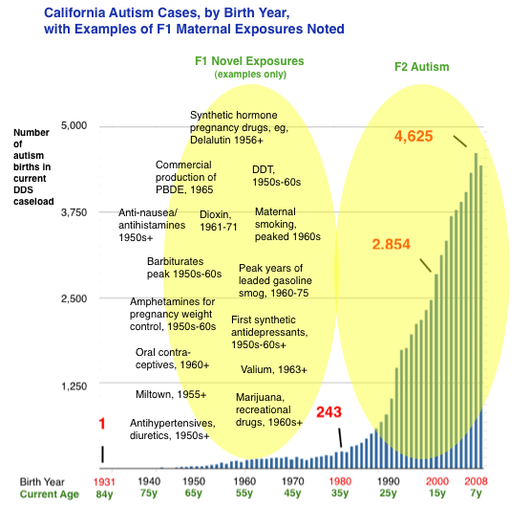

Clearly, many things contribute to the risk of the abnormal early neurodevelopment we label autism: genes (10%), prematurity/birth complications (probably 10%), assisted fertility, especially IVF (small amount), prenatal exposures to neurochemical-disruptive substances such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants (small amount), and more. But for the vast bulk of patients, etiology is unknown. Most research dollars focus on "gene hunting," with some funding going toward investigating proximal fetal exposures. But almost no money has been invested in how exposures have affected the integrity of our DNA. The vulnerable phase of fetal germline synthesis occurs approximately 20-40 years prior to conception, during the parents’ (F1) own fetal development. This dynamic phase involves specification and proliferation of germ cells, epigenetic reprogramming, and the laying of genomic imprints, among other phenomena. And in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, these phenomena occurred in the context of many novel and toxic gestational exposures. Birth cohort data from California’s Department of Developmental Services (see above) indicate that autism births began a quasi exponential ascent starting in the early 1980s. This growth in DDS-eligible autism — a subset of autism involving more severe mental disability and functional limitations, and excluding the “high functioning” segment — has been repeatedly determined not attributable to diagnostic shift or broadening of eligibility criteria.1 California DDS autism numbered about 3,000 in the mid-1980s. Today the autism caseload exceeds 75,000. According to our hypothesis, a portion of this surge may result from developmental dysregulation resulting from molecular effects of old and largely forgotten exposures to the F1 parental germline. For developmental pathology in F2 offspring to have occurred in births in the 1980s and thereafter, germline errors would have occurred during the fetal development of the parental generation, in the 1950s and thereafter. Assuming induced germline errors are playing a role in the autism surge, the next logical question is what exposures increasingly affected the uterine environment in the 1950s, 60s, 70s, exposures that perhaps had been nonexistent or less common in prior decades, centuries, or even millennia? The answer could lie in many evolutionarily novel stressors. For example, maternal cigarette smoking became ubiquitous and peaked in the 1960s. In addition, a wide variety of novel substances were invented, marketed and used as pregnancy drugs, including synthetic “anti-miscarriage” hormones, anti-nausea drugs, painkillers, psychoactive drugs such as antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications, sleeping aids and sedatives, anesthesia, and more. Many of those drugs had powerful endocrine-disrupting or otherwise toxic effects. Medical radiation was applied to many pregnancies. Recreational drug use also surged in the 1960s. We hypothesize that many of these abnormal post-war in utero exposures to the parent generation (F1) could have acted as subtle fetal germline teratogens, inducing mutagenesis, epimutagenesis or both, resulting in dysregulation of development of the subsequent generation (F2). We further hypothesize that fetal germline exposures can result in heritability of autism or related neurodevelopmental disorders due to the likelihood of multiple gametes being affected by the same exposure. It would also result in heterogeneity because, in part, different gametes would be challenged in different ways by an exposure. It would also result in gender differences in offspring owing to epigenomic mechanisms that result in differential phenotypes according to gender, such as imprinting and X-chromosome inactivation. It would also result in demographic differences, since many of the exposures (for example, once-popular prophylactic synthetic hormone treatments) tended to be available to women of higher SES and located in metropolitan areas. Jill Escher fn1: See, for example, Autistic Spectrum Disorders, Changes in the California Caseload An Update: June 1987 – June 2007; and The Epidemiology of Autism in California (2002), noting “The observed increase in autism cases cannot be explained by a loosening in the criteria used to make the diagnosis,” and stating, “Has the increase in cases of autism been created artificially by having ‘missed’ the diagnosis in the past, and instead reporting autistic children as ‘mentally retarded?’ This explanation was not supported by our data.” Moreover, there is no signal or evidence that California’s singularly robust developmental services system has overlooked tens of thousands of mentally and developmentally disabled adults born prior to the 1980s (now over the age of 35) with the striking autism symptomology.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJill Escher, Escher Fund for Autism, is a California-based science philanthropist and mother of two children with severe autism, focused on the question of how environmentally induced germline disruptions may be contributing to today's epidemics of neurodevelopmental impairment. You can read about her discovery of her intensive prenatal exposure to synthetic hormone drugs here. Jill is also president of Autism Society San Francisco Bay Area. Archives

July 2021

Categories |

- Home

-

Expert Q&A

- Eva Jablonka Q&A

- Amander Clark Q&A

- Mirella Meyer-Ficca Q&A

- Janine LaSalle Q&A

- Dana Dolinoy Q&A

- Ben Laufer Q&A

- Tracy Bale Q&A

- Susan Murphy Q&A

- Alycia Halladay Q&A

- Wendy Chung Q&A

- Pradeep Bhide Q&A

- Pat Hunt Q&A

- Yauk and Marchetti Q&A

- Emilie Rissman Q&A

- Carol Kwiatkowski Q&A

- Linda Birnbaum Q&A

- Virender Rehan Q&A

- Carlos Guerrero-Bosagna Q&A

- Randy Jirtle Q&A

- Jerry Heindel Q&A

- Cheryl Walker Q&A

- Eileen McLaughlin Q&A

- Carmen Marsit Q&A

- Marisa Bartolomei Q&A

- Christopher Gregg Q&A

- Andrea Baccarelli Q&A

- David Moore Q&A

- Patrick Allard Q&A

- Catherine Dulac Q&A

- Lucas Argueso Q&A

- Toshi Shioda Q&A

- Miklos Toth Q&A

- Piroska Szabo Q&A

- Reinisch Q&A

- Klebanoff Q&A

- Denis Noble Q&A

- Germline in the News

- Science

- Presentations

- About Us

- Blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed